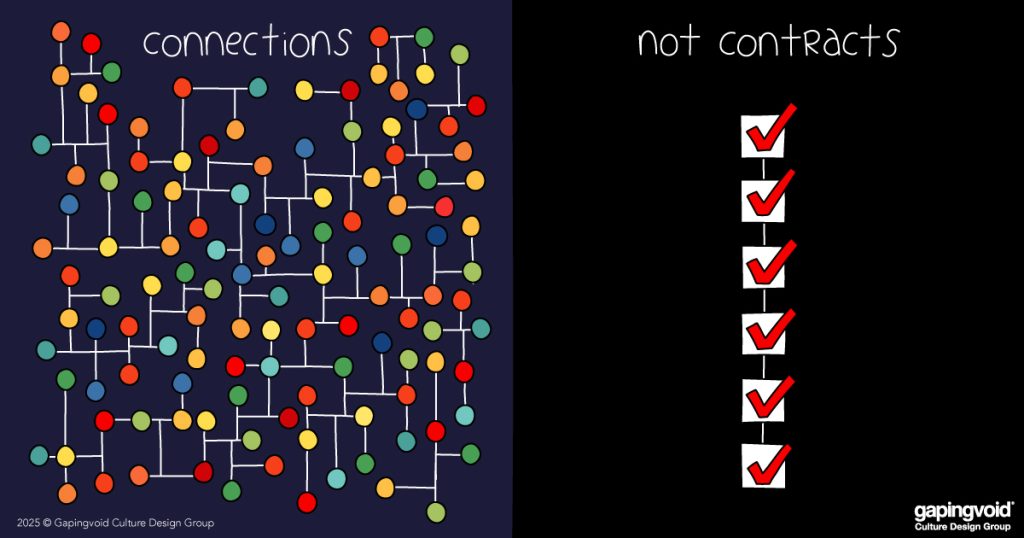

Have you ever had that one colleague you just clicked with? You get how they think, they get how you think, you share a common vision, you’re both honest with each other. As a team, your output isn’t linear, it’s exponential.

Those sorts of connections are littered throughout history.

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

As C.S. Lewis said, friendship begins the moment one person turns to another and says, “What? You too? I thought I was the only one.”

Trouble is, these connections are hard to come by. It feels like serendipity, not something you can replicate reliably.

Except that you can. Create enough opportunities for connection, enough collisions, and some breakthroughs are bound to happen.

One of our favorite parts of this year was partnering with Tradewinds to build community across the federal defense acquisition workforce for people who wanted to outmaneuver the bureaucracy.

Tradewinds operates under the Secretary of War’s Chief Digital and AI Office and was stood up to provide traditional procurement with a tool to acquire technology 10x faster than traditional pathways.

But acquisition professionals across the DoW were stuck in patterns that wouldn’t deliver emerging tech whether a tool was available or not: choosing certainty over speed, feeling disconnected from the mission, caged by “policy won’t let me” thinking. Cynicism to put it plainly.

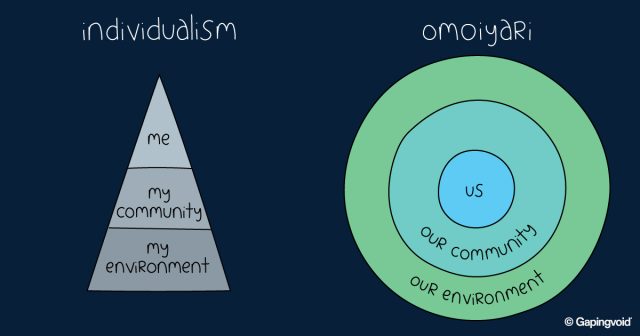

So we built the antidote. The “uncynic” philosophy. New mindsets were designed to break status quo thinking and broadcast through gamified learning tools and experiential training. But most importantly, we built community, bringing a small group of contracting officers and other acquisition professionals ready to push back against cynicism into a single network called the “Uncynic Society.”

The Uncynic Salon was the launch: a one-night-only gathering in a 100-year-old historic loft in LA. No panels. No stale networking. Just off-the-record conversation among folks who refuse to accept “that’s just how it is.”

The goal was simple: help acquisition professionals meet others like them. To realize they weren’t alone in wanting to disrupt outdated systems that no longer serve them or the warfighter.

Acquisition professionals are a core part of an invisible engine that fuels, modernizes and keeps the defense machine running. Nothing moves without them. But they rarely get the credit, and feel the weight of what they’re part of.

This is one of the hardest challenges in leadership: keeping the people working the bureaucracy as motivated as the people at the pointy end of the spear. Both are essential.

You can’t compel connection. You can’t manufacture motivation. But you can create the conditions where both emerge on their own: by filling rooms with the right people, and sending messages that remind people who they actually are.

Making them feel like more than a box on an org chart but someone whose work is high-stakes, whether or not their work is reported on the front pages.

Performance, innovation, and excitement disappear when people forget that. A leader’s job is to make sure they never do.