When’s the last time you thought about your car’s engine?

Probably not for a while.

Most people don’t. Until it breaks.

This sort of thing happened last week, when Amazon Web Services (AWS), which hosts about one-third of the internet, had a massive outage.

Like the ground they walk on, most people don’t regularly think about AWS – until it starts to shake.

The outage lasted 15 hours. 2,500 companies were affected.

It was a series of cascading failures: One system got delayed, which put extra stress on the next system, which rolled over into the next system and so on until the whole thing crumbled.

This illustrates something:

Complexity tends to compound.

And as complexity compounds, vulnerability compounds.

(For AWS, fixing the root cause took 3 hours; fixing the secondary effects took 12.)

If you have one part that talks to one other part, you have one connection and one way for things to go wrong.

If you add a third part, now there are three connections.

Add a fourth, and you’re at six – by the time you’ve added 10, you’re at 45.

45 failure points. 45 vulnerabilities. 45 ways for things to go wrong.

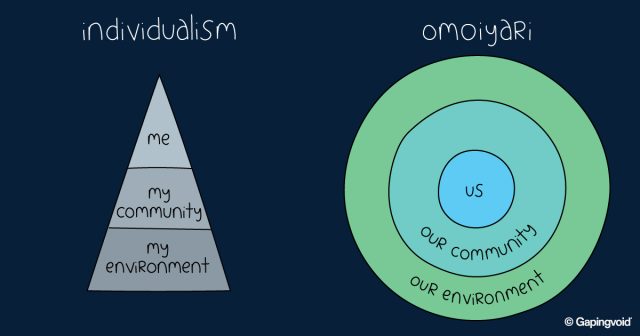

But it’s not just Amazon, we all are somewhat biased to think that the solution to most problems is more.

More parts and features. More protocols and standard operating procedures. More rules and regulations. More stuff.

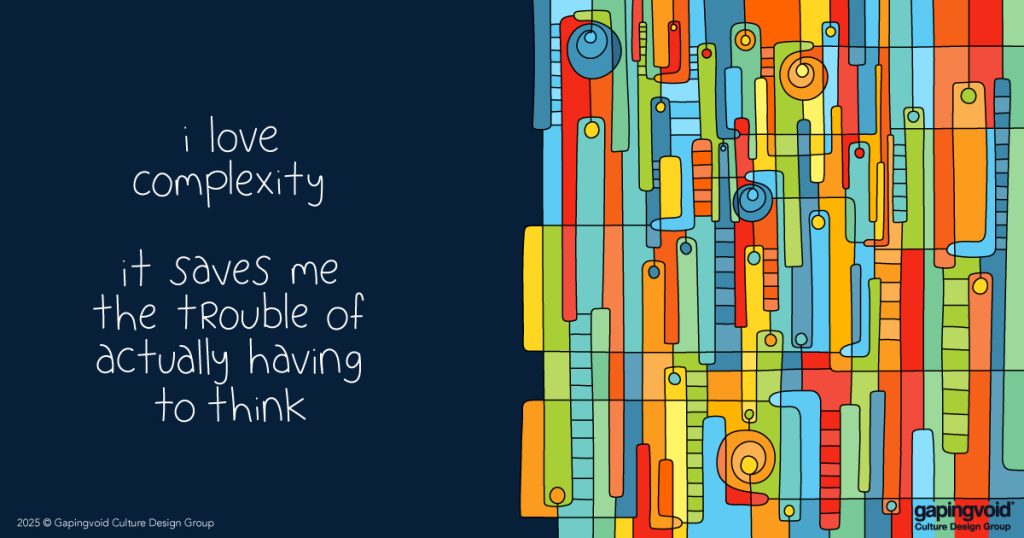

We think we’re slashing through problems when we’re really just slashing heads off the hydra.

First, there’s a mistake. To ensure it never happens again, a new rule is created. But the rule backfires occasionally.

So, an exception to the rule is codified. But too many people take advantage of the exception. A committee gets formed to decide when the exception applies.

The committee makes the wrong call once. Now a managing director steps in to own the whole process and act as the final veto power. Problem solved?

Not quite. People start shortcutting the committee and going straight to the director. We need a rule that says you can only go to the arbitrator after trying the committee.

But wait… sometimes it’s urgent. Okay, let’s codify an exception defining when you can go directly to the director and when you can’t.

Suddenly, the people who thrive at the firm aren’t the ones who know how to solve problems or serve customers, but the ones who know how to play the system.

In the meantime, your lean, agile competitor has produced a new product that solves a real problem for real customers.

Complexity begets complexity, and complexity kills.

The antidote is courage.

The courage to admit that we can’t remove all risk by adding rules.

To admit that we can’t prevent every problem by adding more processes.

To realize that we can’t outsource good judgement to the bureaucracy machine.

The courage to admit that the game is risky. And tricky…