British private clubs got their start for simple economic reasons. Wealthy English landowners needed to come into the city occasionally for business: lawyers, Parliament, that sort of thing. Rather than maintain expensive second homes, friends would “club” together to share a townhouse and split the costs.

It was practical, but something happened in that practical arrangement. The shared space created shared understanding. The people who split costs became the people who belonged.

This became a peculiarly British tradition. By the late 1800s, London had 400 clubs. Today it still has more than double of New York. Three centuries later, some of these clubs have 80-year waiting lists while others struggle to fill their dining rooms.

The difference isn’t the leather chairs or the port selection. It’s clarity.

The clubs that thrive know what they’re for and who they serve. Military officers. Actors. Writers. Horse racing enthusiasts. The clubs that struggle are trying to be everything, keeping old traditions while apologizing for them, wanting prestige without defining what makes them distinct.

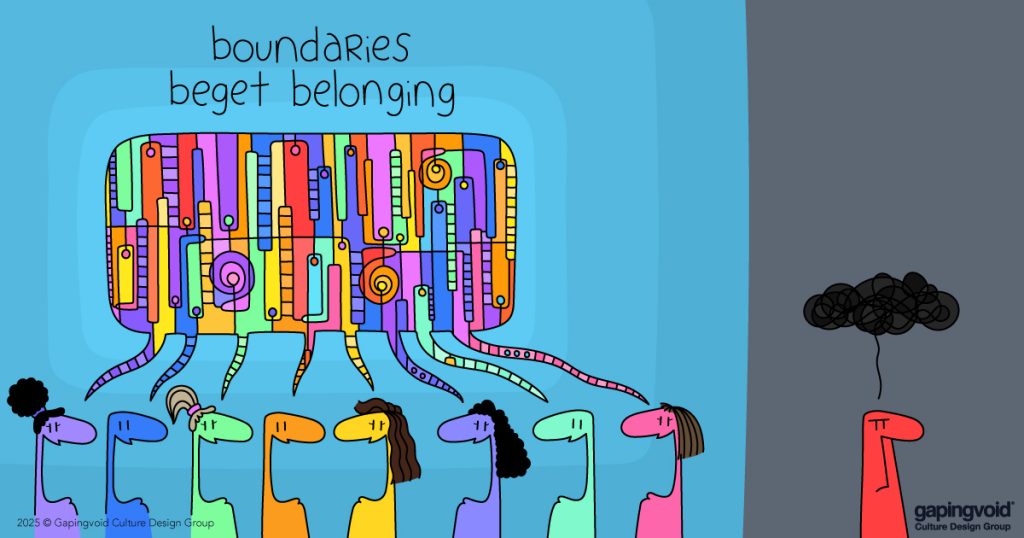

But belonging requires boundaries.

Not because keeping people out is virtuous, it’s not. But because “people like us do things like this” requires an “us.” And an us requires definition.

Your company already knows this. You have a strategy, which means saying no to some things. Chances are you have a brand position too, which means you’re not for everyone and some form of hiring standards, which means some people just don’t make the cut.

You can’t build something meaningful and refuse to say what it’s for.

The club model teaches us something: organizations that endure don’t try to include everyone. They’re clear about their identity, even as that identity evolves. Some clubs that were men-only for centuries now welcome women. They haven’t survived by being vague, they’ve survived by being clear, then changing what that clarity meant over time.

Every choice you make about what your organization is also defines what it isn’t.

That’s how belonging happens.