The NASA astronaut legend, Jim “Houston, we have a problem” Lovell, passed away recently. He was the astronaut immortalized by Tom Hanks’ portrayal of him in the film, “Apollo 13.”

To honor Lovell’s career, his fellow crew members and the whole NASA team made a documentary, with the film producer, Keith Haviland, “Mission Control: the Unsung Heroes of Apollo,” about the people behind the scenes, namely, the people who manned the consoles at Mission Control in Houston. In 2024, he wrote a long blog post about these unsung heroes over on LinkedIn.

What caught our interest from the post was that it wasn’t the more famous Apollo 11 or Apollo 13 that the former console operators remembered most fondly, according to the ones Haviland talked to. It was 1968’s Apollo 8, piloted by Lowell.

Apollo 8 was the mission that first flew a manned spacecraft around the moon, as a precursor to the Apollo 11 moon landing. It was when they shot the iconic and metaphorically significant photo, “Earthrise.” It’s also famous for the crew members reciting passages from Genesis to a captivated world on Christmas Day as they broadcast their view of the lunar surface in real time.

Though it didn’t land on the moon, it did get its fair share of firsts:

- First manned flight of a Saturn V

- First manned vehicle to leave Earth’s gravitational field

- First use of a computer to provide total “onboard autonomy” in navigation

- First manned vehicle in lunar orbit

- First close-up view of another planet

- First exposure to solar radiation beyond the Earth’s magnetic field

- First vehicle to rocket out of lunar orbit

- First manned vehicle to re-enter from another world

But its real achievement was emotional. 1968 had been a challenging, fractious year for the US, with everything from the disastrous Vietnam War Tet Offensive, political dissent, and the assassinations of both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy.

So when the astronauts broadcast themselves reading from the Book of Genesis while flying over the lunar surface on Christmas Day, it uplifted the entire world watching. As one citizen said, “Thank you, Apollo 8, you saved 1968.”

What’s even more remarkable is that this moment of triumph happened less than two years after the disastrous 1967 Apollo 1 fire, which had killed three astronauts and nearly ended the NASA program.

Somehow, they had the leadership, strength, will, and agility to pull it all together despite all the setbacks. A real “phoenix rising from the ashes” story.

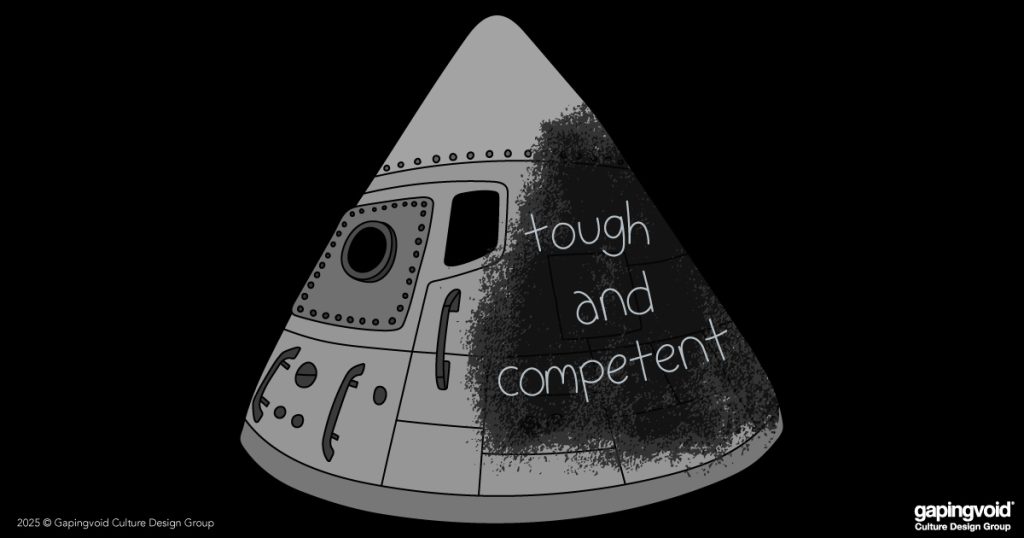

If you read Haviland’s post, you see that this didn’t just happen by itself; it was the result of the “tough but competent” culture that leaders built up after the tragedy. Starting with Flight Director, Gene Kranz.

The Monday after Apollo 1, Kranz gathered his control team and delivered what became known as the “Kranz Dictum.”

He said, “From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: ‘Tough’ and ‘Competent.’ Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities. Every time we walk into Mission Control we will know what we stand for. ‘Competent’ means we will never take anything for granted. We will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills. Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write “Tough and Competent” on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee.”

Two words. Carved into blackboards. Never to be erased.

Every decision, every moment of doubt, every split-second choice was filtered through two simple questions: are we being tough? Are we being competent?

When Apollo 13’s oxygen tank exploded 180,000 miles from Earth, Kranz didn’t panic. He said: “Let’s work the problem, people. Let’s not make things worse by guessing.”

Tough and competent.

While America was falling apart in 1968, three men reading Genesis from lunar orbit proved that language, the right words, embodied completely, can drive decisions at scale across thousands of people.

That’s why they remember Apollo 8. It wasn’t just about orbiting the moon.

It was about two words that became more powerful than any manual.

Thank you, Jim Lovell, your colleagues at NASA, and Gene Kranz for showing us how it’s done.